Introduction: The Science of Interspecies Communication

Effective interpretation of nonverbal communication in companion animals represents a critical competency for responsible ownership. As of 2026, advancements in animal cognitive science and behavioral ethology have further elucidated the sophisticated, yet often misinterpreted, signaling systems of domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) and cats (Felis catus). Misreading these cues remains a primary contributor to relational discord, mismanagement, and compromised animal welfare. This guide provides a formal, evidence-based framework for analyzing and responding to the behavioral sequences exhibited by these species, with the objective of fostering safer, more harmonious, and empirically informed human-animal relationships.

Section I: Principles of Canine Behavioral Signal Analysis

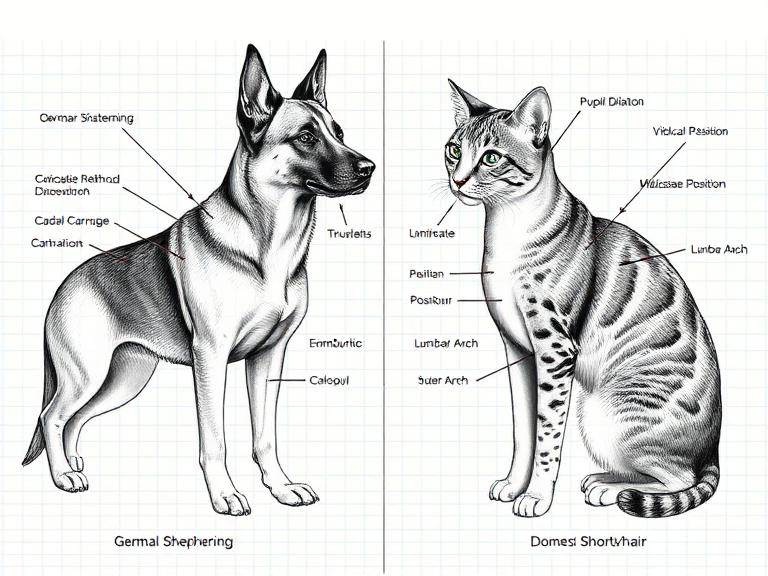

Canine communication is a multimodal system integrating visual, auditory, and olfactory components. Accurate interpretation necessitates holistic observation of the animal’s entire somatic presentation within a specific context.

1.1 Cephalic and Facial Indicators

The head and face offer the most nuanced data. Ocular behavior is particularly informative: a direct, unblinking stare often constitutes a challenge or threat within canine ethology, whereas averted gaze or slow blinking signals deferential or non-threatening intent. The visibility of the sclera (“whale eye”) during a head turn indicates simultaneous fixation and avoidance, a state of conflict or anxiety.

Auricular positioning provides reliable data on affective state. Forward-oriented ears denote focused attention and engagement. Laterally flattened or fully retracted ears are strongly correlated with states of fear, submission, or defensive aggression. Oral indicators include lip-licking in the absence of food (a recognized appeasement or displacement behavior), yawning outside drowsy contexts, and a tense, closed mouth, all of which are markers of stress.

1.2 Posterior Body Communication

Caudal (tail) dynamics are frequently misconstrued. Tail carriage and motion must be assessed relative to the individual’s neutral baseline and breed-specific morphology. A high, rigid tail with rapid, restricted movement signifies high arousal, which may be positively or negatively valenced. A medium-height tail engaged in broad, sweeping motions typically accompanies affiliative greetings. A tail held low or tucked between the hind limbs is an unequivocal signal of fear, anxiety, or active submission.

Overall body tonus is equally critical. A relaxed, fluid posture indicates a neutral state. A rigid, immobile stance signifies high alert and potential preparation for action. The “play bow” (front quarters lowered, hindquarters elevated) functions as a meta-signal, framing subsequent actions as playful and non-threatening.

1.3 Integrated Behavioral Sequences

Practitioners must learn to interpret behavioral sequences rather than isolated gestures. For instance, a dog may approach a stranger with a stiff body, high tail, and direct stare (investigative/tense), then offer a play bow (attempting to de-escalate and initiate benign contact). Growling is a vital, distance-increasing warning; its suppression through punishment is contraindicated, as it may lead to escalation without precursor signals.

Section II: Deciphering Feline Behavioral Semiotics

Feline communication is characterized by greater subtlety and reliance on nuanced signal gradations. Misinterpretation often stems from applying canine social frameworks to an asocial predator’s behavioral repertoire.

2.1 Cephalic and Vocal Signals

Feline ocular communication is distinct. The slow blink, involving deliberate eyelid closure, is a well-documented affiliative signal. Dilated pupils in ambient light can indicate high arousal from fear, excitement, or predatory focus. Auricular semiotics are precise: forward-facing ears denote interest or curiosity, while ears rotated laterally or flattened (“airplane ears”) signal irritation, fear, or offensive aggression.

Vocalizations require contextual analysis. While purring is often affiliative, it also occurs in states of distress, pain, or parturition, likely functioning as a self-soothing mechanism or care-soliciting signal. Chirping or chattering is directed almost exclusively at prey or prey-representative stimuli.

2.2 Posterior and Somatic Displays

The tail serves as a precise mood barometer. A vertical tail, especially with a hooked tip, signifies a friendly, approachable state. Piloerection (fur standing erect) along the tail and spine indicates a frightened or threatened animal attempting to appear larger. Intense, rhythmic lashing from side-to-side is a clear indicator of agitation and a probable precursor to aggressive action.

Tactile behaviors are often misinterpreted. Allorubbing (rushing against a person or object) is primarily a scent-marking behavior using facial pheromones, denoting environmental familiarity and comfort. Exposing the abdomen can be a sign of trust in a secure environment, but it is not an invitation for tactile interaction for most cats; ventral contact is frequently perceived as threatening. Kneading, a remnant neonatal behavior, is associated with states of contentment and relaxation.

Section III: Applied Principles for Daily Management

The practical application of this knowledge is paramount. The following protocols are recommended for integration into daily husbandry.

- Respect for Calming and Cut-Off Signals: Owners must learn to identify and respect behaviors that signal a need for space. In dogs, these include turning the head away, lip-licking, and moving away. In cats, tail twitching, skin rippling, and ear rotation are definitive “stop” signals. Forced interaction following these cues damages trust and may provoke a defensive response.

- Contextual Analysis for Accurate Interpretation: No signal exists in isolation. A wagging tail in a dog with a stiff body and fixed stare is not indicative of a friendly greeting. A purring cat that is simultaneously tail-lashing is likely overstimulated, not content. The environment, antecedent stimuli, and totality of the animal’s posture must be synthesized.

- Proactive Environmental Management: Use signal recognition to pre-empt conflict. Observe early signs of stress (e.g., pacing, hyper-vigilance, hiding) during events like guest arrivals or pre-veterinary travel. Implement positive reinforcement, pre-emptive decompression, and structured retreat spaces to mitigate anxiety before escalation occurs.

- Documentation and Pattern Recognition: Maintaining a simple log of behavioral incidents, including antecedent events, the precise behavioral sequence, and the consequence, can reveal patterns invisible to casual observation. This data is invaluable for owners and essential for professional behavioral consultations.

FAQs:

Q: Is a growling dog always being aggressive?

A: No. Growling is a communication of discomfort, stress, or fear. It functions as a warning to increase distance. An animal that growls is providing essential information that a threshold has been crossed. The appropriate response is to calmly remove the perceived stressor or the animal from the situation, not to punish the communication.

Q: Why does my cat suddenly bite during a petting session without apparent warning?

A: This phenomenon, often termed “petting-induced aggression” or overstimulation, is common. Cats frequently provide subtle warning signals (tail twitching, skin rippling, cease of purring, tense posture) that are missed. The bite is a terminal cutoff signal after earlier, milder cues were ineffective. Learning to identify and cease interaction at the earliest warning sign prevents this outcome.

Q: Are certain dog tail wags definitively “friendly”?

A: No single wag pattern is universally “friendly.” While a loose, broad “helicopter” wag often accompanies affiliative states, it must be assessed in concert with the rest of the dog’s body language. A wagging tail solely indicates arousal; the emotional valence of that arousal (happy, anxious, tense) is discerned from other somatic cues.

Q: What is the most common error in interpreting animal signals?

A: The most prevalent error is anthropomorphism—ascribing human emotional complexity and rationale to animal behavior. This leads to misinterpretations such as labeling a dog as “guilty” for house-soiling (a submissive response to owner demeanor) or a cat as “spiteful” for scratching furniture (a normal marking and grooming behavior). Adherence to species-specific ethological understanding is essential.